Women correspondents covering politics, conflicts and news events for television channels face daunting odds but are driven by the desire to make a difference.

When stone-pelting began in north-east Delhi’s Maujpur area on February 23 this year, 26-year-old Sukirti Dwivedi was one of the first reporters – and the only woman – on location. As multiple waves of bloodshed, property destruction and rioting were unleashed, and the police stood by doing nothing, all the television correspondents there began to fear for their lives.

“It was unsafe for everyone, not just girls,” says the firebrand NDTV correspondent. At one point, she found herself in the midst of a group of young boys, barely 17 or 18 years old, with stones and rods in their hands, their faces covered, and she noticed with a sense of foreboding that she was the only girl around. “That’s when I got scared,” she admits, adding that some senior citizens nearby came to her rescue.

After two days, as soon as the situation was under control, Sukirti – who was raised in Kanpur and had wanted to be a television journalist ever since she was a teenager – was back in the field. What she saw in the aftermath of the riots made her cry. “I broke down when I saw the school there completely burned down. The thought that there would have been children in there left me shuddering.”

Seven days of covering this kind of crisis can take a toll on anyone. “In many situations, being male or female doesn’t matter,” says Sukirti, adding that many of her male colleagues covering the riots had sleepless nights just as she did.

Broadcast journalism has seen more women joining its ranks in the past few decades, with women reporters now in parliament, covering elections, rallies, crime, corporate affairs and travelling far and wide to the interiors of the country for human-interest stories.

Most media headquarters are located in big cities, and while the job comes with its fair share of challenges even for seasoned metro-dwellers, girls from smaller towns appear to have more fire in their bellies.

Archana Shukla, associate editor at CNBC TV18, was the first girl in her family to move out of Jamshedpur and start working as a journalist in Mumbai. It was a tough call for her parents 15 years ago when the microbiology student first made the move.

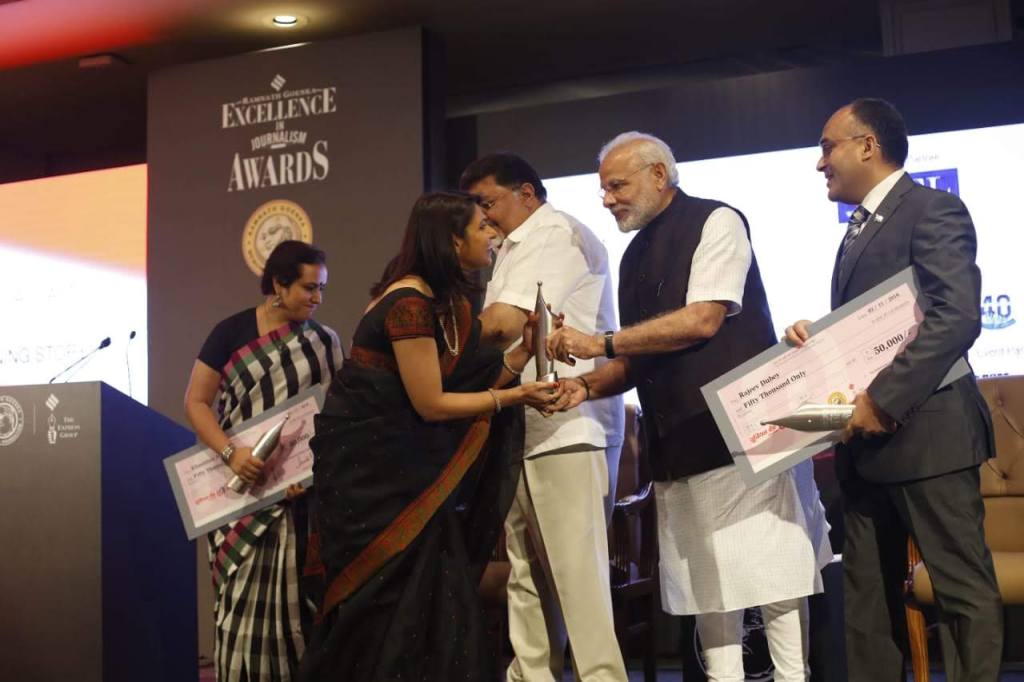

“My parents had their doubts. It didn’t help that the Bollywood film Page 3 starring Konkona Sen Sharma had just released and they were concerned about the safety of this profession,” she smiles. Over the years, Archana made it a habit to call her mother at least once a day wherever she was. The 36-year-old eventually made her parents proud by winning six awards for excellence in journalism.

But it’s one thing to allay your parents’ fears and another to deal with your own. A job such as this puts you in harm’s way more often than others, and Archana has learnt to keep her wits around her especially when she travels to the country’s hinterlands to cover social and political issues. Phone networks are often sketchy and places to stay are ill-equipped for women.

“It’s there at the back of your mind, a little fear when there is unrest. But news-gathering in television is teamwork, and we move as a crew, which is safer,” she shares.

While covering stories in far-flung areas of Bastar and Marathwada, Archana also had the experience of being mobbed, with people outraging and saying, “Media-wale kharab hote hain (mediapersons are bad).” She has now devised her own way to deal with them: “I take time, I listen to them, and then I explain myself. I remain sensitive to their concerns even while I tell their stories to the world.”

For correspondents covering politics, the playing field is still uneven. But Pallavi Ghosh, senior editor (politics) at CNN News 18, who has been covering Congress news for the past 18 years, sees positive signs of change. “From two or three female journos covering Parliament 18 years ago, there are about 25 now whenever Parliament is in session. It’s no longer lonely out there,” she informs.

Besides broadcast, the digital medium has also given women more avenues to step out and report news. There are now hundreds of women reporters across the country, working full-time or as stringers for websites, YouTube channels and social-media platforms, including bilingual ones.

For Pallavi, covering politics is exciting even if it’s not always smooth. “My first brush with a mob was in Baghpat, Uttar Pradesh, at an election rally in 2004. It was a huge, unruly crowd, and they went crazy to see a woman reporter amongst them. Things went out of control but my cameraman pulled me out of it,” she narrates. After that, she says, she was not scared anymore.

On the day we speak to her, she is busy following Madhya Pradesh politics as former Congress leader Jyotiraditya Scindia joins the rival BJP. Quickly checking facts before going on air, she is collected and in control. Her years of experience have taught her a thing or two about dealing with male politicians.

“Some of the netas (political leaders) are very condescending and they think we women are just trying to earn some extra pocket money by stepping out to work!” says the 44-year-old indignantly.

“They even ask me, do I earn so that I can shop? So, yes, initially it was tough, but over the years more women have come into the field and that has helped. Also I think it’s important not to smile at their sexist jokes. You have to make it clear to them that you mean business.”

But the biggest challenge that on-field reporters face in India is not mobs or sleazy politicians but toilets! While Sukirti has learned to control her bladder until she finds a petrol pump when she is travelling, Pallavi carries a packet of Pee Safe in her bag.

In contrast, Archana, who often goes to villages, says, “Travelling has taught me lots of lessons in survival. Indians are hospitable people. I have made friends in several towns, and I use their toilets!”

The times are tough, and it’s physically a challenge, but these ladies are out there with vigour and resilience. After years of reporting and seeing things for what they really are, do reporters still remain idealistic about the profession?

“I was very idealistic when I began,” shares the young Sukirti. “I used to think, sarkar sunti hai (the government listens). For instance, if I report on street lights missing in a certain place, I thought the government would take action. But three years in journalism and my idealism is in pieces now.”

The thought that journalists could make a big difference has faded over time, adds Pallavi. “I am more pragmatic and less idealistic now,” she admits.

Despite their own disillusionment with the system, their value systems make them walk on the path of unbiased and credible reporting. As Pallavi puts it, “You should be able to look into the mirror and say, ‘I did my job well’.”

First published in eShe’s April 2020 issue

Syndicated to MoneyControl.com