Public libraries have been low on government priorities in the past few years; now COVID is threatening our few brave community libraries too.

By Shweta Bhandral

There was a time when India had a robust system of public libraries. However, in the past few years, more than 5000 public libraries have shut shop. Maintaining a public library is a state subject, and each state has its own priorities.

For example, going by a 2018 survey, the government of Uttar Pradesh, which has a population of more than 200 million, supports only 20 rural libraries, while the government of Kerala, with a population of 34 million, supports around 7,600.

That is why it has mostly fallen to non-governmental organisations (NGOs) around India to take the initiative and launch community libraries taking books to sections of society that most need them.

The Community Library Project (TCLP) in Delhi is one of the most robust of them. What started in 2009 as a book club now serves 4,000 children. TCLP has four branches in Delhi-NCR that give free access to books to everyone. TCLP is also a learning lab that follows the best practices of the trade and trains librarians and teachers.

Its director Mridula Koshy says most people in India limit the use of books to learning and knowledge, which is not their only purpose. The celebrated author says, “When we read a book, we imagine other cultures. Books help us in thinking and exploring our curiosity. We also acquire some facts from them, but thinking is most important.”

Along with its reading room, storytelling sessions and workshops, the library has an empowering system of student councils, which motivate younger kids and help the librarians run the centre. Mridula, 50, believes that civic institutions like libraries can mediate between citizens and the government, or citizens and the marketplace. That’s why they are essential for the fabric of our country.

“Different communities require different interventions,” adds Lakshmi Karunakaran, the program director of the NGO Hasiru Dala, which works for the welfare of waste-pickers in Karnataka.

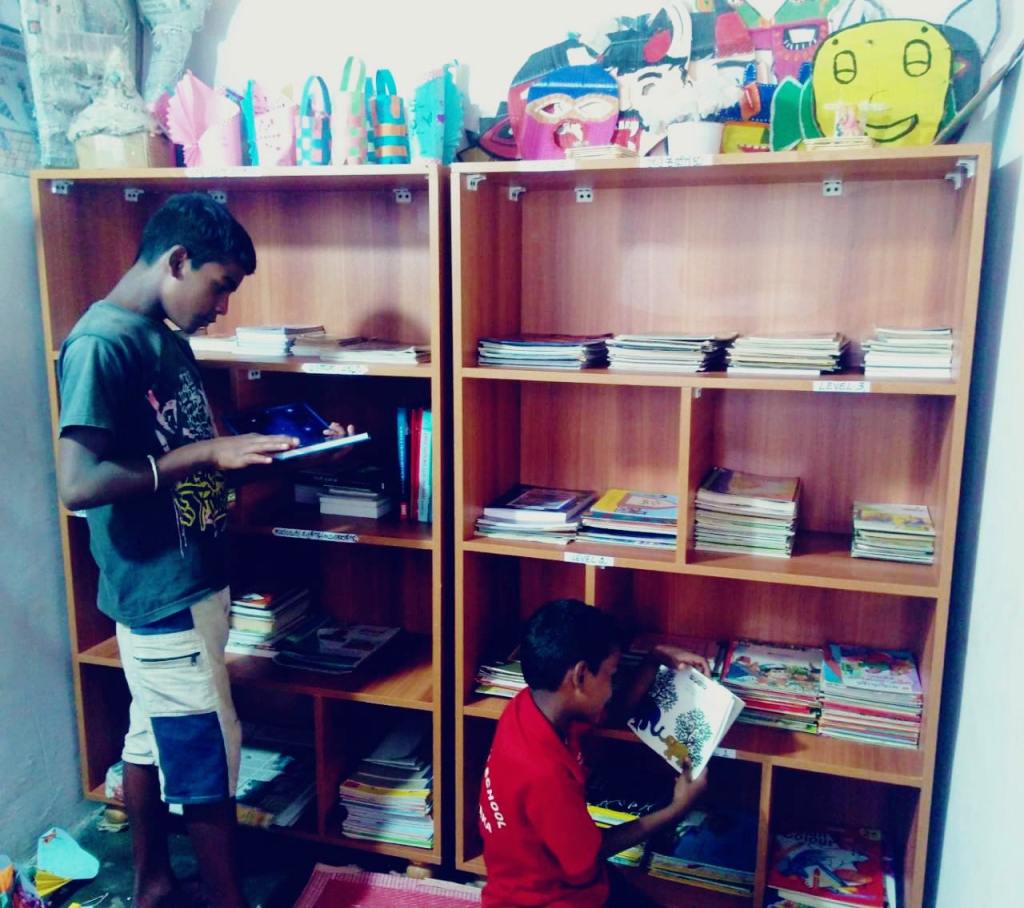

“The waste-picker community that we deal with needed multidimensional intervention, so we thought what’s better than books and an art room?” says the 37-year-old, who initiated the Buguri community library project in 2017, and which now has three centres across the state. Issues like child marriage, drug abuse and domestic violence are the biggest challenges of this community. That is why there was a need for day-to-day engagement with its children.

Along with reading room programmes, discussions and borrowing books, the Buguri library also conducts creative art therapy sessions for kids. A significant impact of the library project has been a change in how children are viewed in the community now. The library has a Book Box that also travels to locations without centres for conducting reading sessions.

Inspired by the work done by the Delhi and Karnataka community libraries, 34-year-old Kolkata girl Ruchi Dhona left her corporate job to set up a similar project in Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh. After a trial project in 2018, she went to Spiti in 2019 with a grant from Wipro, taking her project Let’s Open a Book to every school in the valley.

The challenging terrain and sub-zero temperatures make it difficult for civil-society organisations to carry out interventions in such areas, and Ruchi has been a lone soldier running the show in Spiti with some help from the Meenakshi Foundation.

Serving 600 students now, Ruchi says, “The idea is to build a culture of reading among children. The focus of the initiative is government primary schools, where we begin by setting up small libraries, followed by working with the teachers to help them understand how to use these books and how they can engage the children. We are helping to revive the local public library as well.” She wants to inspire children in Spiti to write their own stories.

With COVID and lockdown, however, all these fantastic projects have taken a big hit. For Ruchi, the biggest challenge is internet connectivity. She says, “These are quite challenging times for community libraries since these spaces are not just about physical books but also one-on-one interactions. All of us are finding ourselves in completely uncharted territory. The best bet is digital.”

Living in Dharamshala, since Spiti banned entry for outsiders, she is now creating audio and video books and sharing them with children in the valley via a local volunteer.

Though connectivity is not an issue in Bangalore and Delhi, the Buguri community library and TCLP are facing a lack of digital devices, and the fact that their members do not have the money to buy data plans.

Buguri has started to connect with their community via conference calls. Children who did not have a phone could join their friends for a read-aloud session. Lakshmi and her team created a play Maya & Thoonga to spread awareness about COVID amongst the children in the waste-picker community. Their creative healing sessions are also now being run via calls.

Each centre has a WhatsApp group to stay in touch with the children of their area. The library also started a podcast in four languages on a local radio channel called Radio Active, which helped connect with children and even parents without mobiles or internet.

The constant threat of coming in contact with the virus while dealing with medical waste; being marginalised by society; the withdrawal symptoms of having no access to substances; escalating domestic violence, poverty and hunger – the problems amongst the waste-picker community increased several-fold during lockdown.

Lakshmi tells us, “There is an even stronger need to enable access to books for our children now. We started sending out a reading and activity books with every ration packet that we distributed.”

On its part, TCLP concluded that during lockdown, the libraries had two crucial responsibilities: first, to continue to provide access to quality reading material; and second, to act as a centre for information that members and their families desperately need as most TCLP members are part of the migrant community who live in Delhi.

They have 10 WhatsApp groups for sharing audio and video stories with their members. This online library is called ‘Duniya Sabki’ and the student council members, librarians, teachers and volunteers contribute to it. Stories and articles for all ages are regularly uploaded on TCLP’s Facebook page, YouTube and on their website too.

Still, as Mridula puts it, “An online library can never be a fraction of what a free physical library can be. The latter brings multiple people and multiple interests into multiple engagements in one location. A digital library can only ever be an addition to a physical library.”

During this lockdown, the distribution of food took over every other need. Charity from all over went into supplying ration. TCLP staff also did some relief work in collaboration with other NGOs despite the fact that one of their significant funders backed out.

Unhappy with the turn of events, Mridula says, “People’s right to food security, which is a right of citizenship, cannot be met by non-profit organisations distributing ration or by resident-welfare associations cooking food. These are commendable and necessary efforts, but today charity has reached its limit, and incredibly the government has still not been called out for their failure to meet citizens’ needs. The current thinking that only ration relief needs to be funded and all other needs are to be viewed as competing interest is going to hurt the very people it purports to help.”

Research shows that the longer children stay out of school, the higher the risk that they will not return. Mridula tells us, “Our library is planning to open in a minimal way because to continue to stay closed puts our members at increasing risk.”

The Buguri library has also taken a few steps towards opening. “As the lockdown eased, with parents moving out to work, we saw a drop in the engagement in online classes. So, we continued our work through a hybrid model with small group contact sessions keeping in mind the safety requirements. That way, we can have a deeper engagement with children,” says Lakshmi.

First published in eShe’s September 2020 issue

Syndicated to Money Control